|

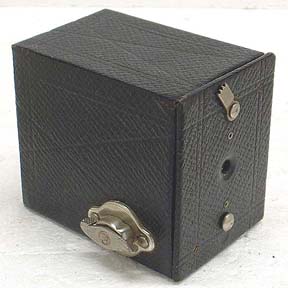

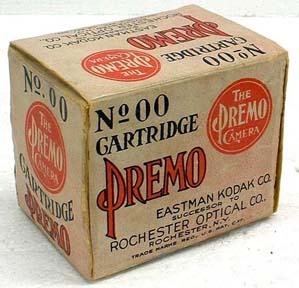

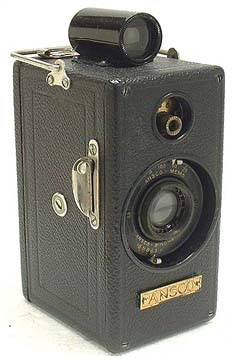

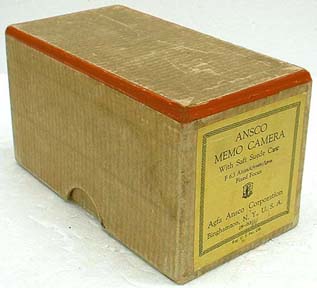

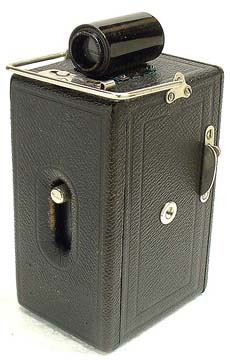

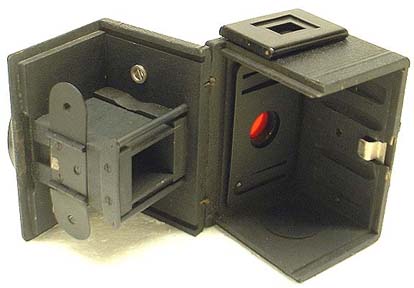

Copyright © 2005 David Silver. THREE CLASSIC BOX CAMERAS FOR 35MM FILM BEYOND LEICA, BEFORE CONTAX, THERE WAS 35MM FOR EVERYBODY! by David Silver    The Ansco Memo of 1927 (left), Kodak No. 00 Cartidge Premo of 1916 (middle), and Zeiss Ikon Unette of 1925 (right). Most camera collectors know that the advent of 35mm technology was rampant with radical new designs and novel approaches to miniaturization. The earliest successful attempts at bringing the convenience of 35mm cine film to the still camera market in 1913, specifically the Tourist Multiple in America and the Jules Richard Homeos in France, both exemplified the high quality and mechanical ingenuity, as well as the correspondingly high prices, that manufacturers strived to attain. Equally complex cameras would soon follow, but by the late 1920's the Leica established a benchmark for 35mm design, the early 1930's saw the Contax reinforce that concept, and then in 1934 Eastman Kodak leveled the playing field when they introduced the Retina and a standardized daylight loading cartridge for all 35mm cameras to use. Meanwhile, despite the traditional historical connection with marvels of mechanical progress, there were other cameras from this period of 35mm evolution that popularized the new medium without the need for cutting edge technology or lofty price tags. Their names are often forgotten when the conversation turns to the formative days of 35mm photography, but they were already stabilizing the "minicam" market while so many others were still in the dark. In this article I'm going to look at three of them, all simple box cameras, and all successful in their own ways. One is a charmer, one is famous and fondly remembered, and one is surprisingly rare.  The remarkable little No. 00 Cartridge Premo of 1916, Eastman Kodak's smallest box camera. Eastman Kodak was the first to embrace 35mm film in a simpler and more affordable camera in 1916. George Eastman had already proven the logic of mass-market appeal with the runaway success of his original Kodak in 1888, with successive models in the 1890's, and then most strikingly with the Brownie of 1900. Make a camera that any man, woman, or child could use, make it affordable, make it seem to be a necessity for every modern home and family, and then reap the profits from the expanded sales of film. A logical extension of this strategy, combined with the sudden availability of excess 35mm film stock from the budding movie industry, was the remarkably tiny No. 00 Cartridge Premo.  The colorful original box for the No. 00 Cartridge Premo. Based outwardly on the Brownie series of amateur box cameras, this little charmer was the smallest model Eastman Kodak made, it was a product of their Rochester Optical Division, and measured only 2 5/8 inches tall, 2 1/4 inches wide, and 3 1/8 inches long. Like the earliest Brownies, the body of the No. 00 Cartridge Premo was reinforced cardboard and covered with thin fine-grained imitation leatherette. The lens was a single meniscus and the shutter was of the "automatic" reciprocating sector type offering time or instantaneous mode. In lieu of a viewfinder, there were diverging lines on the top and side that gave the photographer a sense of the image area. Lifting the film winding key disengaged the rear box section for loading, and the body simply pulled apart. It used a special roll film, which was nothing more than a strip of nonperforated 35mm film stock with numbered (for the exposure counting ruby window on the back) paper backing on a traditional daylight loading spool, and made exposures 1 1/4 x 1 3/4 inches. While no one would mistake the No. 00 Cartridge Premo for one of those expensive marvels of mechanical engineering, I'm sure they would be impressed by its singular appeal and extraordinary value. When introduced in 1916, the camera was priced at a mere seventy-five cents, and a roll of film for six exposures was only a dime! No wonder it remained a popular model with children and families on a limited budget, but production ceased in 1922 when Eastman Kodak began to dissolve the Rochester Optical section.  The simple pull-apart body and interior detail of the No. 00 Cartridge Premo. The Ansco Company used a different strategy in their initial approach to 35mm in 1926, using the 35mm movie film stock exactly as it came, complete with perforations, and without any need for numbered paper backing or spools. They developed a simple box camera with a spring-loaded internal "claw" in the back, driven by a short downward thrust on a small external button, which engaged the perforations and accurately advanced the film from one cassette to another, thus assuring each frame was perfectly positioned shot after shot. This, of course, was the Memo camera, and it remains one of the most beguiling yet innovative designs Ansco ever produced.  A perfect example of the 1927 Memo camera from Ansco. The Memo was advertised late in 1926, and was available for purchase immediately in 1927. Simply yet ruggedly constructed of light wood with genuine leather covering, and featuring attractive nickel-plated and black enameled fixtures, it stood about 4 1/2 inches tall, 2 5/8 inches deep, and only 2 1/4 inches wide. Initially the camera was equipped with a fixed focus Ilex-Ansco Cinemat 40mm f6.3 anastigmat lens, but a fine Wollensak Velostigmat was soon available, as well as several focusing Wollensak and Bausch & Lomb optics, including a fast f3.5 version. These were all mounted on an Ilex "readyset" leaf shutter with speeds 1/25 to 1/100 plus B and T, and each click of the trigger would also advance the mechanical exposure counter. The camera sported a proper optical viewfinder mounted on top and was fitted with a nickel-plated carrying handle. A sliding latch released the back door for loading. A cassette holding enough 35mm film for fifty 18mm x 24mm exposures was fitted into an upper cavity, the film leader was pulled down and started into the lower cassette, the back was closed, the film was advanced a couple times with the "claw" mechanism, the exposure counter was reset, and the camera was ready to shoot. In their earliest form the cassettes were wooden cubes, then metal cubes, and most commonly seen in a later rounded shape. The first few thousand cameras had a shutter release trigger that was unprotected and probably fired accidentally on occasion, so a trigger guard was introduced on all subsequent versions.  The fancy original box for the Ansco Memo. Unlike the No. 00 Cartridge Premo, the Memo was designed to appeal to a greater and more sophisticated cross section of the market. The simplest version of the camera, with the fixed focus lens, complete with fitted soft suede carrying case, sold for only $20, a fraction of the cost of a Leica, and a fifty exposure load of film was only fifty cents. At a penny a picture, you might assume the Memo would produce amateurish results, but the lens and shutter were more than adequate for the task, in many ways superior to most cameras of that time, and in typical ideal situations rendered professional quality images with regularity.  The back of the Ansco Memo, showing the unique sliding mechanism for advancing the film. More importantly, the Memo was never intended to stand alone, but was part of an entire photographic system that included an enlarger, a positive film printer, a copier, and several projectors, all at reasonable prices. There were also at least two special versions of the Memo, a fancy finished wood model that is rarely seen today, and an olive drab Official Boy Scout Memo that came with a matching green carrying case and for which Ansco offered a specific Boy Scout Memoscope projector. Despite its unqualified success, the Memo fell victim to the sudden economic changes of the depression, and the once promising market for such a system based amateur camera soon disappeared. By 1930 Ansco, now merged with Agfa, ceased production of the Memo and was selling off the remaining units at deep discount prices. They would revive the Memo name in a radically different model nine years later, but well past the standardization of the 35mm format.  The Memoscope projector, part of the system supporting the Ansco Memo camera. The third and final member of our trio of 35mm box cameras was announced by Ernemann of Germany towards the end of 1924. The Unette miniature box camera was a sensible cross between the extreme simplicity of the No. 00 Cartridge Premo and the broader market goals of the Memo. It used special nonperforated paper backed rolls of 35mm film and relied on a simple shutter like the former, while offering better construction and a higher profile like the latter. Its overall dimensions were also somewhere in between the other two cameras.  A rare original 1925 Unette from Zeiss Ikon. The Unette entered the market late in 1925. It usually featured Ernemann's typical "readyset" shutter for instantaneous or time exposures, and a 40mm f12.5 meniscus lens with smaller settings at f18 and f25, but there was also a version with a plainer shutter housing that only allowed the maximum aperture. The body was constructed of very light wood, delicately assembled, and covered with an attractive fine grained synthetic leatherette. A pop-up frame viewfinder was mounted on top, and many were fitted with a single metal loop strap lug. To load the camera, a sliding latch on the side was released, the entire body hinged apart in the most unusual diagonal fashion, and then a ruby window in the rear allowed the photographer to keep track of the exposure numbers on the paper backed spools of 35mm film.  The rear view of the 1925 Zeiss Ikon Unette. Early in 1926 the format size of the Unette was standardized at 22mm x 33mm, and the camera's overall dimensions were slightly enlarged to accommodate this. The reason for this change is that Ernemann had also introduced in 1925 a compact folding bellows camera called the Bobette, offering the same 22mm x 33mm format on its own special spool of 35mm film and a system of developing and printing accessories, and they wanted to coordinate the two camera lines to simplify their catalog. However, for a very brief period, the original smaller version of the Unette provided a format of 18mm x 24mm. That first version, an exceptional example of which is illustrated in this article, is extremely rare today, and the McKeown's Price Guide to Antique and Classic Cameras shows no record of sales in the past thirty years!  The unusual hinged body and interior detail of the 1925 Zeiss Ikon Unette. Towards the end of 1926 Ernemann merged with Contessa-Nettel, Goerz, and Ica to form the manufacturing giant Zeiss Ikon. The Unette camera (and the Bobette) continued until 1930, but, despite their initial successes, they would also fall victim to the economically stressed market of the great depression. Zeiss Ikon would return to 35mm a few years later, but in the form of their highly upscale Contax camera rather than another simple model for the average person. The No. 00 Cartridge Premo, the Memo, and the Unette together represent an important yet neglected part of the evolution of 35mm camera technology. While collectors and historians praise the prowess and ingenuity of those more famous makes and models, these three little box cameras successfully demonstrate how better is not always best. With simple construction and simple solutions, they achieved simple pleasing results, and placed the novel medium of 35mm film in the hands of everyone. For collectors today, they further represent a fascinating and valuable legacy from that extraordinary period of technological experimentation. As a final note, several months ago a rare original 1925 18mm x 24mm Unette sold on eBay, the first such sale recorded in decades, for an astonishing $1026! However, I frankly wasn't surprised. It was just one more remarkable feat...by a simple 35mm box camera! Copyright © 2005 David Silver. All rights reserved. This article first appeared, in slightly edited form, in the July 2005 (issue #157) Camera Shopper magazine. If you'd like to reprint the article, acquire secondary rights, or inquire on the availability of new articles, please feel free to contact the author at silver@well.com, thank you! BACK to the International Photographic Historical Organization article page! GO TO the International Photographic Historical Organization home page! CONTACT the author, David Silver, for more information! |