|

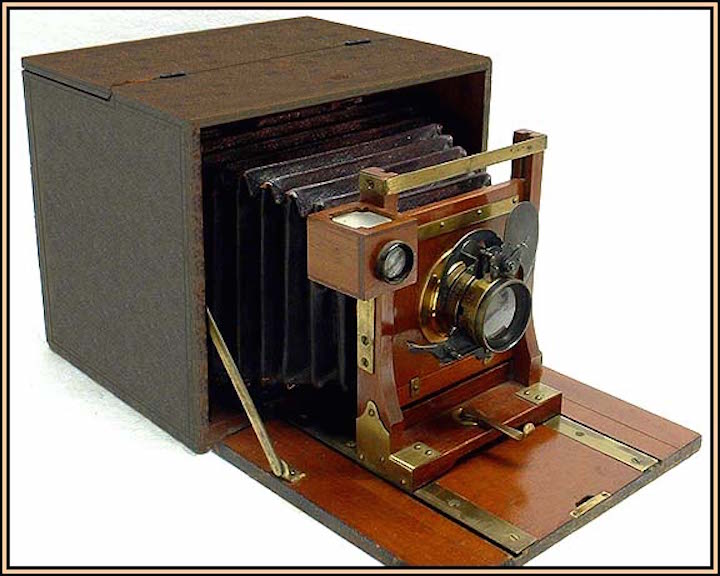

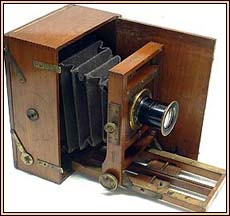

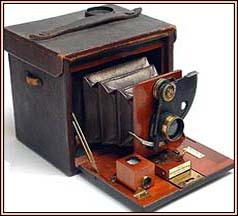

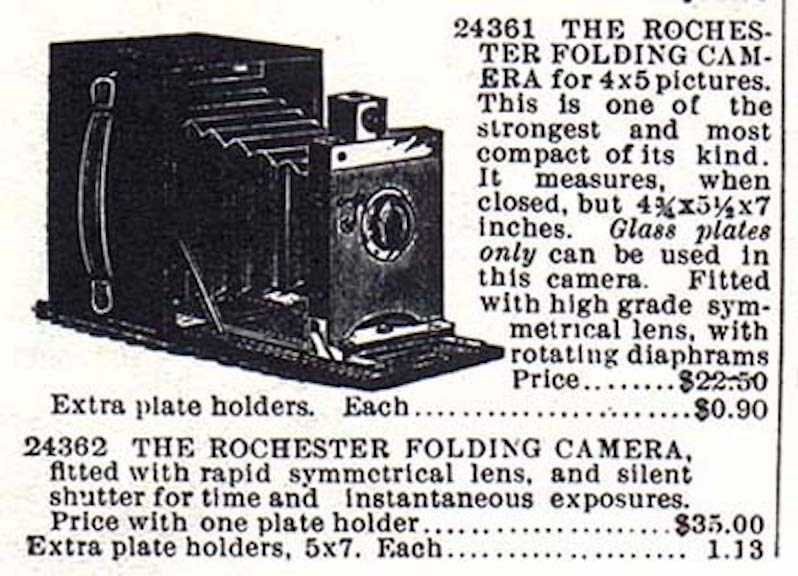

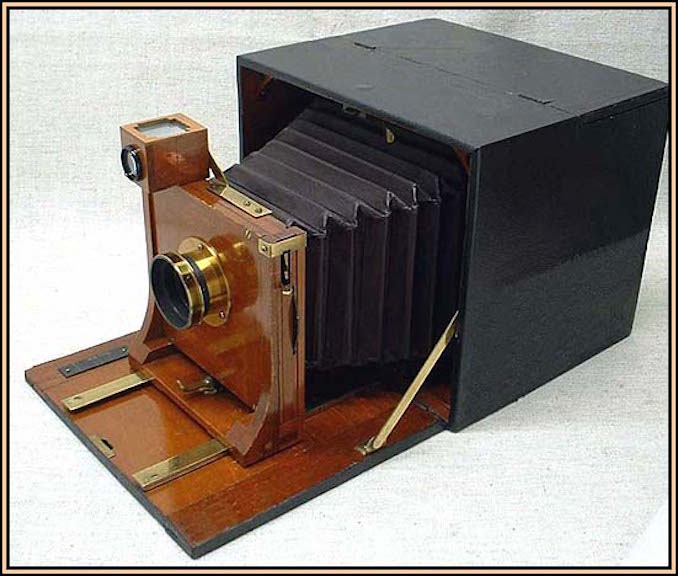

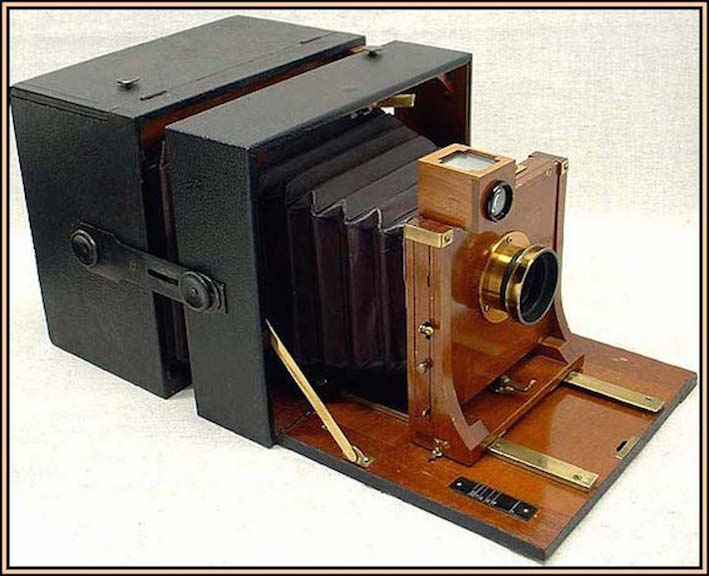

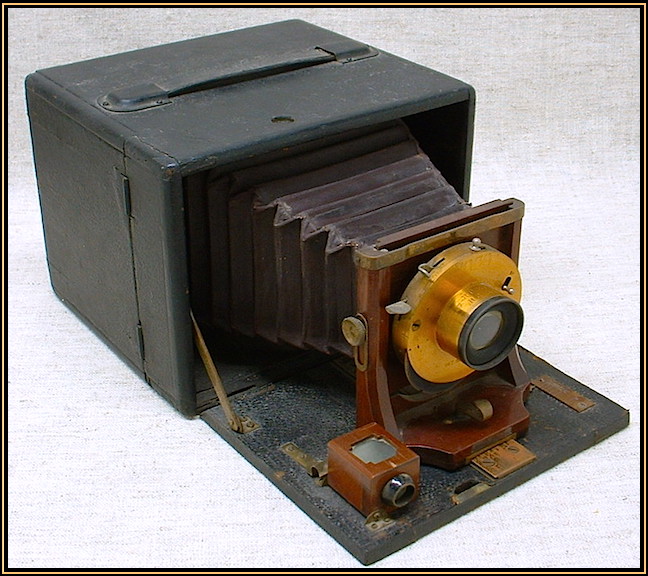

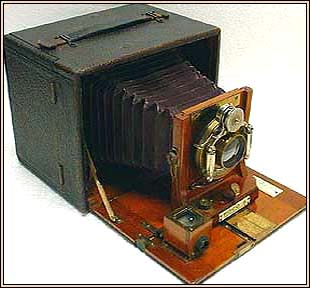

Copyright © 2005, 2012, 2018 David F. Silver THE 1892 FOLDING ROCHESTER A LEGENDARY EARLY AMERICAN SELF-CASING FOLDING PLATE CAMERA by David F. Silver  An original 1892 Folding Rochester self-casing folding bellows camera in 5 x 7 inch format. An important innovation in the evolution of photographic technology was the "self-casing" folding bellows camera popularized in the United States in the early 1890's. These American cameras, which used the standard dry glass plates of their time, were the first to integrate the lightweight collapsible flexibility of traditional view cameras into a supportive exterior body shell that also served as a protective case and provided easier portability. Pearsall's Compact Camera of 1883 was an aborted early attempt at such a design, but apparently did not progress past the prototype stage, despite premature advertising announcing its arrival. Two years later in 1885, the Lucidograph from the Blair Camera Company succeeded commercially and functionally with its odd side-saddle interpretation of an integral external case, and it remained in production for a surprising number of years, but it was always an awkward and inelegant solution that evolved no further. Another ambitious entry was the Gibbs Camera of 1888, sporting a more European flavor with beautiful polished tropical wood construction and a tripod mount built into the unusual flip-under rear door that also served as a base, but it failed to generate market interest. The self-casing concept finally took root, and is most often credited today, with Eastman's Folding Kodak "satchel" camera of 1890 (actually only using flexible roll film at first, but then in 1892 adapted for glass plates as well). Further refined design elements were presented in the impressive Henry Clay camera from the American Optical Company starting in 1891. Each of these models and manufacturers in turn contributed their own stylistic and structural aspects to the general self-casing concept, but it was yet another camera that followed, which is notably scarce today and too often neglected in the conversation, that would establish the true blueprint for all the rest to come.    Three important earlier interpretations of the self-casing folding bellows camera concept, upon which the "Folding" Rochester camera improved; the Blair Lucidograph of 1885 (left), the No. 4 Folding Kodak "satchel" camera of 1890 (middle), and the American Optical Company's Henry Clay of 1891 (right). The Rochester Camera Manufacturing Company was founded in 1891 by H.B. Carlton (the brother of W.F. Carlton, who founded the similarly named Rochester Optical Company in 1883), and immediately went into the production of standard view cameras and related accessories for professionals and advanced amateurs. Noting the success of the earlier Lucidograph series, and then the sudden impact of the Folding Kodak and the Henry Clay, the new Rochester firm sought to improve upon and emulate the self-casing design with a model of their own that would provide even lighter weight and more simplified function without sacrificing high quality or efficiency. The result was the Rochester Folding Camera of 1892 (or for simplicity’s sake, collectors and historians today refer to it as the “Folding Rochester”). Like its predecessors, it was internally a simple view camera, a collapsible bellows stretched across a focusing track between a front lens standard and a rear ground glass screen, built into an integral boxy case that provided support when shooting, and immediate protection when stored. However, it incorporated the varied aspects of its predecessors into a more logical and cohesive whole for the first time.  A later advertisement for the Folding Rochester camera, dating from 1894, listing both the 4 x 5 and 5 x 7 inch formats, and illustrating the more rare "plain face" version. The Folding Rochester was generally available in 4 x 5 or 5 x 7 inch format, or 6 1/2 x 8 1/2 inc format by special order. The body of the camera featured a leather covered external wooden case with a large downward hinging front door, a much smaller hinged door in the back, and an access door across the upper rear area. A button hidden under the leather at the top edge of the case released the front door, which then dropped and braced into horizontal position with a pair of simple brass struts, and provided a sturdy bed of beautiful polished mahogany with dual brass focusing tracks. Reaching into the camera body, the photographer grasped the front standard upon which was mounted the lens and shutter, pulled it forward along the calibrated tracks, extending the maroon red bellows behind it, and secured it with a generous brass locking lever at whatever chosen focus distance. The front standard assembly displayed more fine mahogany construction and brass highlights, and supported a top-mounted waist level reflex viewfinder. Another hidden button under the leather below the rear edge of the case released the top door and this exposed the internal mechanism for loading the glass plate holders. It also provided access to a pivoting clasp that opened the back door so the photographer could see the ground glass viewing panel when more precise focus was necessary. There was enough room in the rear area to store two double plate holders when the camera was not being used.  The back of the Folding Rochester, showing the top door for loading or storing the plate holders, and the rear door for viewing the ground glass panel when more precise focusing was required. While the Lucidograph was awkward to assemble, the Folding Kodak was unnecessarily bulky with its non-camera "satchel" amenities, and the Henry Clay was rather delicate with its fussy track sections, the Folding Rochester offered extremely easy opening and set-up, a simpler no-frills external case, and a much sturdier bed and focusing track arrangement. It was also advertised with a selection of the better quality shutters made by Prosch or Bausch & Lomb, similar to the those used by the other top manufacturers, with the addition of one particular shutter that was designed specifically for the Folding Rochester and complemented its unique personality. This was "The Rochester" shutter, a spring activated mechanism with an external flying wing sector that fired with a most satisfying clang. Outwardly similar to the Folding Kodak's original sector shutter, "The Rochester" was more compact, much easier to use, provided a range of five speeds with a simple tension adjustment, and even had a provision for time exposures. It was assembled as the barrel section between the elements of a superb Gundlach Optical Company Symmetrical lens, the lens of choice on the majority of the Folding Rochester cameras, and was fitted with a revolving aperture wheel providing four stops.  "The Rochester" shutter, which was unique to the Folding Rochester series. The Folding Rochester was also produced in a "plain face" variation, which is quite rare today, despite appearing frequently in their period advertising. Again available in both 4 x 5 and 5 x 7 inch formats, it featured a larger square wood front standard that completely concealed an integral spring driven rotary shutter. A thin brass plunger on the side of the standard cocked the shutter with a single push, and a simple pivoting trigger released it. A tensioning spring protruded from the other side, where a slotted channel provided three different speeds. To date, the author has only seen three complete intact examples of these encased shutter "plain face" variations, and they are exceptionally handsome cameras. Some of the earliest period advertising also described a special split-body model, in the 5 x 7 inch format only, similar to the Folding Hawk-Eye cameras from Blair, which provided a limited degree of rear swings and tilts. This version was never illustrated, it was apparently only available directly from the factory by custom order for a significantly higher price, and no complete intact examples of this variation were known to exist until the author finally acquired one in 2012. Another was later located in a private collection in 2015. Furthermore, there were notes in the Rochester catalogs suggesting an intent to provide an interchangeable roll film holder option for the all 5 x 7 variants, which would mount in the body in place of a removable focal plane frame section, but very few of the known Folding Rochester cameras exhibit this internal feature, and a Rochester roll film adapter has never been seen.  A very scarce, and very beautiful, "plain face" version of the Folding Rochester, with the rotary shutter completely concealed in the fancy finished mahogany wood front standard.  The only known complete intact example of the exceedingly rare "split-body" version of the Folding Rochester camera, acquired by the author in 2012, until a second was located in a private collection in 2015. The last and most rare of all the Folding Rochester variations appeared for only a very brief time at the very end of the line's limited production. Despite a few vague descriptive period advertisements that alluded to its existence rather than illustrated it, no complete example seemed to have survived, and for many years it was considered more of a legendary "missing link" than a reality. This was the Folding Rochester "Poco" variation, and it was the direct connection between the Folding Rochester series and their extremely popular Poco series of self-casing folding plate cameras that would expand and sell in great numbers well into the twentieth century. It wasn't until 2018 that an intact original example finally emerged. True to the descriptions in those ancient advertisements, the camera still featured the robust body construction of the earlier Folding Rochester variations, with the Rochester model name proudly stamped in gold, but now the loading access door was on the side, the external case was more compact, the reflex viewfinder was moved to the bed, a single focusing track replaced the twin tracks, and there was an improved lighter front standard supporting its newly designed fancy brass "Poco" shutter, the name for which the Rochester Camera Manufacturing Company would soon become most famous. While enticing bits and pieces of the Folding Rochester Poco variation have been found over the years, as of 2018 this one remains the only complete original example. With its discovery, the entire evolution of the Folding Rochester line is now known and well illustrated.  The recently discovered "missing link" at the end of the Folding Rochester series, the Folding Rochester "Poco" camera, the rare final variation, that gave birth to the popular Poco series of cameras they would continue to produce for many years.   The gold Rochester stamp inside the side door (left), and the unique "Poco" shutter (right), on the only known intact example of the Folding Rochester "Poco" camera. The year 1892 was noteworthy for the number of other self-casing designs that entered the market, including the Folding Premier from the Rochester Optical Company and the previously mentioned Folding Hawk-Eye from Blair, but it was the Folding Rochester that initially brought together the most logical aspects of the concept for the many models that would follow. While it may not have been the very first such camera, it was certainly the most influential formulation upon which American photographic firms would base their own further designs. The Rochester Camera Manufacturing Company produced the Folding Rochester for only about two years, although they continued to sell remaining stock well after that. Meanwhile their newly introduced and improved Poco series of self-casing plate cameras that replaced the Folding Rochester in 1894 were a major success from the start. The rival Rochester Optical Company introduced a similar competitive line, the Premo, around the same time. These were soon followed by a massive wave of self-casing American folding plate cameras that swept through the photographic market for years to come, culminating in the classic press cameras of the early to mid 20th century, most exemplified by the Speed Graphic from Graflex, that dominated the world of professional photography.   Two typical common examples of the many immediate descendants of the Folding Rochester; their own Poco A of 1895 (left), and the Rochester Optical Company's Pony Premo No. 6 of 1898 (right), both in the most common 4 x 5 inch format. Today the Folding Rochester is among the most scarce and coveted, and certainly among the least known, of the early self-casing American folding plate cameras. Given its mere two years of manufacture, few were produced, and since the original publication of this article in 2005 and up through 2018, the author has personally recorded or accounted for only nineteen reasonably complete intact examples, the majority in 5 x 7 inch format. So far the ongoing count includes thirteen in standard configuration with traditional external shutters on the front standard, five "plain face" variants (two of which are split-body), and finally the single exceedingly rare "Poco" version. Most of these examples exhibit dry and peeling exterior leather (oddly enough, a problem also seen with the Henry Clay, its primary and most similar competitor at the time), but the camera's overall value due to its rarity and historical significance outweighs the impact of this common cosmetic flaw. As the least known and still a vitally important progenitor of the American self-casing concept, the Folding Rochester certainly deserves its legendary status as an enigmatic classic and a precious link in the evolution of 19th century photographic technology.  The ROCHESTER model brand, proudly stamped in all Folding Rochester series cameras. Copyright © 2005, 2012, 2018 David F. Silver. All rights reserved. This article was originally published, significantly edited for length and content, in the July 2005 (issue #157) Camera Shopper magazine. It's presented here, in its intended full form, with additional updated text, notes, and images added in 2012 and 2018. If you're interested in reprinting this article, or wish to solicit new works on the history of photography, please contact the author, David Silver, at silver@well.com, thank you! The INTERNATIONAL PHOTOGRAPHIC HISTORICAL ORGANIZATION: BACK to the organization's contents page! GO TO the organization's home page! CONTACT the organization's moderator and webmaster for more information! |