Copyright © 1996, 2002, David Silver.

BUYING CLASSIC

CAMERAS II

by David Silver

Usable collectibles for medium format? Why not?!

To hear some people talk, you would think the sudden growing interest in "medium format" cameras was just another new fad in photography. And a potentially expensive fad, for that matter! But where does the jaded photo-techno-junkie or the semi-serious wannabe-pro look when the potential of the tiny 24 x 36 frame in 35mm film seems exhausted? What, you might ask, would the professional photographer do?

Well, it comes as no surprise today, after 35mm dominated the photographic market for the past thirty years or more, that so many people are now "discovering" medium format for the first time. After all, that's indeed what the professionals are doing! The irony here, however, is that medium format is hardly new. In fact, it's older than this century! [The author notes in 2002: "This article was written in 1996 during the sudden peak in medium format rollfilm SLR camera sales, but the market has since stabilized with a returning interest in 35mm and greater leaning towards digital!"]

A simple beginning to medium format on rollfilm:

The benefits of medium format in all its various frame sizes, as made available through venerable old #120 rollfilm, are well documented. Even the smaller 1 5/8 x 2 1/4 inch "half frame", such as produced by the Mamiya 645 series of cameras, provides an image more than triple the area of 35mm. And, more traditionally, as with Hasselblad or classic Rolleiflex, when #120 is shot in 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inch square, the image is a full third bigger than that! Still, as history shows, this is nothing compared to how it all began.

Medium format on rollfilm, as we still recognize it today, originated with Eastman Kodak's first Folding Pocket Kodak camera of 1898. Using #105 rollfilm, introduced specifically for this model that same year, the camera produced images 2 1/4 x 3 1/4 inches, over six times the area of a modern 35mm film frame! By the standards of that time, however, the No. 1 Folding Pocket Kodak was actually a marvel of miniaturization. Extensive use of aluminum in the body provided an unprecedented lightness, and the remarkably compact design was achieved with a pop-out folding bellows that automatically set the camera for universal focus. Unlike most other popular cameras around the turn of the century, including earlier clunky and chunky attempts at practical medium format rollfilm models, it really was small enough to fit in a pocket. It also featured a simple internal lens and shutter assembly that allowed unusually user-friendly operation. After a seventeen year run of production, during which it evolved and influenced whole new lines of cameras to come, the No. 1 Folding Pocket Kodak is hardly rare today, but it remains a prized collectible of great historical import with a fair market value of up to $100.

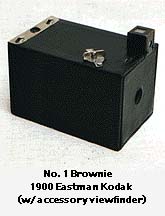

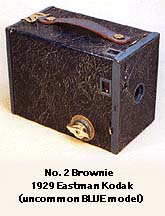

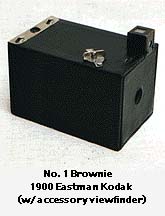

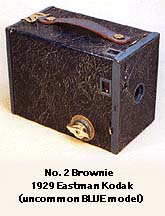

In 1900 the first Brownie camera, another undeniable classic from Eastman Kodak, provided a smaller 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inch format on new #117 rollfilm. [The author notes in 2002: "This camera line's entire fascinating story is told in far greater detail in a much earlier article I wrote for another periodical and was later reprinted in Photo Shopper."] The next year the larger No. 2 Brownie offered the same healthy 2 1/4 x 3 1/4 inch format as the No. 1 Folding Pocket Kodak, but this time on even newer #120 rollfilm. Both of these exquisitely simple box cameras, featuring inexpensive cardboard construction and a price tag that anybody could afford, would revolutionize photography by making it all so accessible to the masses. And, of course, they did so while offering medium format quality results. The original Brownie, later designated the No. 1 Brownie, was available until 1915, while the No. 2 Brownie was manufactured, in ever evolving style, for an unbelievable thirty-two years!

Now you're probably wondering why Eastman Kodak had introduced three different cameras in such a short time using three different rollfilms, but all producing the exact same 2 1/4 inch wide results. It's true, #105, #117, and #120 were all actually the same 2 1/4 inch wide film stock rolled onto virtually identical spools, but Eastman Kodak put different exposure number patterns on the paper backing of these films to match the locations of the "ruby window" on the different camera models. Incredibly, despite the overwhelming success of #120 in particular, it wasn't until the 1940's that Eastman Kodak finally came to their senses, eliminated #105 and #117 as superfluous products, and then put all the various exposure number sequences for all the various format possibilities on the paper backing of #120 rollfilm alone. In this way, #120 replaced the earlier films and would provide many formats by itself. Nevertheless, it's ironic to note that the vehicle for medium format on rollfilm today, our "professional" format, had its humble beginnings with the Brownie, the simplest snapshot camera of nearly a century ago!

So where do we go from here? With a heritage this old, there must be all sorts of opportunities for collectors to acquire classic usable examples from the evolution of medium format cameras. As luck would have it, there is, and I'm going to provide a little sampling to whet your appetite! After seeing these, remember, there are thousands more out there waiting for you to discover. But first, a few simple words of encouragement and advice...

As Steve Anchell stated so eloquently last month in the premier issue of Photo Shopper, when delving into the world of medium format photography for the first time you must be prepared for, "...a more careful, introspective approach to image making." This is even more important when the cameras are vintage in nature. Collectors have to understand that these are mature old machines that have already seen a lifetime of work and would probably prefer to remain "retired"! When looking for a less expensive classic usable camera, hoping to avoid paying those big bucks for a modern rig, don't be overly critical of funky focusing, lack of metering, manual controls, and non-coated optics. Take your time, give them a chance, have some respect, and never forget, unlike all those spiffy new products, these oldtimers usually go up in value after you buy them! Besides, let's face it, as honest collectors, it's all of the above "complaints" that give these vintage cameras their undeniable charm. And so, to illustrate that there are indeed respectable alternatives to the familiar world of Hasselblad, Mamiya, Bronica, ad nauseum, let's now look at two perfectly usable medium format camera styles from the past that are largely ignored today.

Medium format folding rollfilm cameras:

By the 1930's, on a direct line of evolution from the Folding Pocket Kodak, folding rollfilm cameras in general had become the dominant expression in the photographic market. With better lenses and shutters, matched with that generous 2 1/4 inch wide format provided by #120 rollfilm, there were many notable models worthy of appreciation.

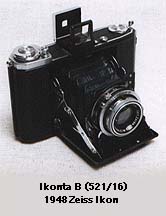

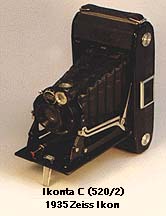

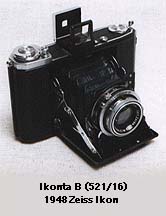

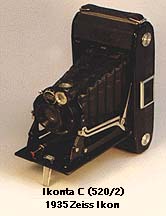

At the top of the list in terms of usability for many collectors today, the great German firm of Zeiss Ikon produced for nearly thirty years a classic line of folding cameras, the Super Ikonta, featuring a different sized model for each of the formats available on #120 rollfilm. Unfortunately, its market value is so often a reflection of its professional quality and desirability that most of the models are quite expensive today. Zeiss Ikon collectors are fanatical and the Super Ikonta is one of their favorites. Instead, I want to recommend two simpler folding rollfilm camera lines from Zeiss Ikon, the plain Ikonta and the usually neglected Nettar. For example, the Ikonta B (model 521/16) of 1948 can come equipped with an excellent Zeiss Tessar 7.5cm f3.5 lens and Compur Rapid shutter providing speeds from 1 to 1/500 plus B. On the down side, it requires scale focusing where you have to "guesstimate" the distance (unlike the Super versions with their coupled rangefinders). However, it does take twelve razor sharp 2 1/4 inch square shots on a roll of #120, it folds flat enough to slip easily into a coat pocket, and with this preferred lens and shutter combination can be found for about $125. A comparably equipped Nettar, the various models of which are remarkably similar in outward appearance to the Ikonta line, is even less. Plus, whether Ikonta or Nettar, there are many different sizes and models to choose from. In either case, and whatever size and vintage of Zeiss Ikon folder you pick, there is no reason to insist on the Tessar lens. The much cheaper Novar Anastigmat lenses, often relegated to collectible status only, are actually very nice indeed and capable of outstanding warm results.

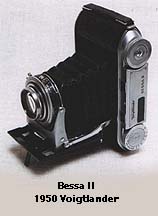

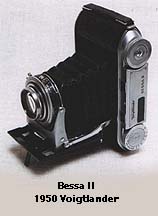

Another great German firm, Voigtlander, is as old as photography itself, and from the 1930's through the 1950's they also offered a superior line of folding cameras for #120 rollfilm. The Bessa cameras were available in a number of lens and shutter combinations to meet every budget, providing an exciting variety of models for the collector. Many of the cheaper versions are absolute bargains in the $50 to $75 range during this currently Zeiss-happy market. The collector looking for a usable example, however, might do better to stick with the more advanced models. My personal favorite, although the most expensive, is the Bessa II of 1950. Sporting a fine Color Skopar 105mm f3.5 lens in a Compur Rapid shutter, with fully coupled split-image rangefinder for focusing, this marvelous machine handles so well that you'll have to wonder why they ever stopped making them! The down side? Supply and demand has driven the asking price over $400, and nearly twice as much when fitted with the superb Color Heliar lens! The up side? Can you imagine pin sharp 2 1/4 x 3 1/4 inch negatives taken with the same ease as any modern 35mm camera? What's more, can you imagine color transparencies that size?! Now, you can't do that with your Hasselblad!!

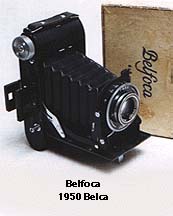

While Zeiss Ikon and Voigtlander are two of the recognized giants of German camera production, there are many interesting smaller manufacturers also worthy of attention, such as Beier, Welta, Agfa, and Belca. The latter produced a particularly simple and affordable folding #120 camera, the Belfoca of 1952, that I've found to be a very capable shooter. Its non-coated 10.5cm f4.5 anastigmat lens is mounted in a simple "readyset" shutter providing a limited range of speeds from 1/25 to 1/100 plus B, but what more do you need? Besides, remember, we're talking about the "more careful, introspective approach" here! And it's an outstanding example of what even a very inexpensive folding camera can do with the full 2 1/4 x 3 1/4 inch format. Anyway, for under $50, this product of USSR occupied Dresden deserves more than a little attention, if not a little more respect.

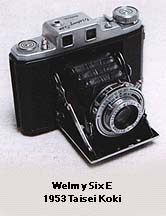

So far we've seen the origins of medium format rollfilm cameras in the United States, then their increasing quality and sophistication in Germany, but what about other parts of the world? How about Japan, for example? Okay, maybe we don't think of Nikon or Canon when the discussion turns to vintage medium format. Maybe not! But other Japanese manufacturers, producers of great folding #120 cameras in the German tradition, included Olympus, Minolta, Konishiroku (Konica), and Kuribayashi (Petri). Taisei Koki released a particularly nice little square format folding #120 camera in 1953, the Welmy Six E. It operates around a surprisingly sharp Terionar 75mm f3.5 lens in a very smooth "Compur" style shutter with speeds 1 to 1/200 plus B. Like the classic Ikonta it very much resembles, it requires scale focusing, yet offers a very sturdy carriage and a choice of eye-level or waist-level viewfinders. As a collectible and usable camera, this extremely serviceable machine is well worth its current $75 market value. And don't forget to look for comparable models from those other great Japanese companies, as well as some of the outstanding classic products, like the Iskra and Moskow, now coming out of the old USSR.

Medium format twin lens reflex cameras:

While folding rollfilm cameras were ascending to their position of dominance in the amateur markets of the 1930's, the "twin lens reflex" or TLR style of #120 camera was becoming a favorite of the professional photographic world. The TLR was basically an advanced type of box camera with an oversized waist level viewfinder attached to the top and synchronized with the taking lens, allowing the taking lens to be focused automatically in conjunction with the viewing lens. While never as light or portable as the folding rollfilm cameras, they were normally very rugged, usually well equipped with top quality lenses and shutters, and provided the best viewing and focusing compromise for ideal artistic composition. Although many photographers today still acknowledge the ability of this type of camera, the TLR is sadly neglected while expensive newer "single lens reflex" or SLR designs assert themselves on the market. The result is a forgotten treasure trove of medium format usable collectibles!

The name Franke & Heidecke is nearly synonymous with the TLR. They introduced their first Rolleiflex camera in 1929 and, in an unintended homage to medium format's humble beginnings with the first Brownie camera, used #117 rollfilm to make 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inch exposures. They would later convert to the more traditional and versatile #120 film. The Rolleiflex, in all its many incarnations over the years, is undeniably the most treasured professional TLR among upper scale collectors and users. As you might expect, the prices reflect this! However, there is a better way to get your hands on a still usable yet affordable classic Franke & Heidecke camera. Buy a Rolleicord instead! The Rolleicord is the often belittled brother to the Rolleiflex, usually sporting a slower lens and simpler shutter, but also selling for less than half the price. Even the Rolleicord I of 1934, for example, remains a very usable vintage TLR. I recommend the leather covered version, which is much easier to find and keep in good condition than the fancy art-deco nickel-plated original model of 1933. The Zeiss Triotar 7.5cm f3.8 lens is a bit soft by modern standards, but makes for especially flattering portraits and is plenty sharp at smaller apertures. The Compur shutter will do all you ask of it, but be sure to check the speeds thoroughly before you buy because these are often harder to repair on TLR's. Such an old soldier may feel like all knobs and angles at first, but, once you get used to it, you'll enjoy its solid heft and sturdiness. Plus it's a steal at under $150. Don't forget to consider the many later versions of the Rolleicord as well.

If you insist on having all the finest bells and whistles with your TLR, the Japanese may have cornered the market in reasonably priced, high quality models, some of which we'll consider shortly. But they also produced many dependable low cost #120 rollfilm "flexes" through the 1950's, most of them using fail-safe external lens gearing and archaic "ruby window" film indexing, while offering reliable shutters and sharp lenses. With prices ranging from $40 to $100, these are the ideal "first" TLR's for the neophyte medium format user and collector. A favorite of mine is the Ricohflex, from the Riken Optical Company, an amazingly competent little picture taker that I have turned to frequently over the years for ultra sharp 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inch color transparencies. Available in a number of slight model variations made between 1950 and 1956, and readily found at swap shows today for under $75, I cannot recommend this underrated gem enough!

At the higher end of the Japanese offerings, look no further than Yashica for a fabulous selection of top flight TLR's, some sure to be future classics. The best of the lot is the sterling Yashica-Mat 124G, a pricey #120 rollfilm model highly sought among collectors and users today, but Yashica made many others as well. For example, close consideration should go to the Yashica-Mat LM of 1957. This is a marvelous camera, sporting a fine Yashinon 80mm f3.5 lens, an extremely smooth Copal shutter, and even a selenium light meter. Sleek styling, good balance, and readily accessible controls highlight the sound thinking that went into this beauty. For about $120 it would be difficult to find a better camera in this style and price range.

Finally, back in the United States, there were a number of able and not-so-able excursions into the TLR design in the years following World War II. A pair of the more famous models, showing both ends of the quality spectrum, were the simple yet rugged Kodak Reflex of 1946 and the strikingly complex Automatic Reflex made by Ansco in 1947. These have more value as collectibles than usables today, the former selling for around $45 and the latter for up to $175. However, there was also the Graflex Corporation, which marketed that all-American product of 1950, the Graflex 22. This workhorse TLR, using #120 rollfilm to make typical 2 1/4 x 2 1/4 inch square exposures, was actually manufactured by another firm known as Ciro, wore a relatively sharp Graftar 85mm f3.5 lens, and was powered by a Century Synchromatic shutter from Wollensak. While not the most graceful of designs, and weighing more like a boat anchor than a camera, it can still take pictures that would impress even the most discerning modern photographer. Oh, and what if it doesn't impress that jaded modern photographer? Well, at only about $60 fair market value, it may not be priced by the pound, but think of what a wonderful doorstop it would make!

Copyright © 1996, 2002, David Silver. All rights reserved.

This article first appeared, as edited here from a longer original manuscript, in the January 15, 1996, issue of Photo Shopper magazine. If you'd like to reprint the article, purchase secondary rights, or discuss the possibility of acquiring new articles, please feel free to contact the author at silver@well.com, thank you!

BACK to the International Photographic Historical Organization contents page!

GO TO the International Photographic Historical Organization home page!

CONTACT the author, David Silver, for more information!

|