Copyright © 1996, 2002, David Silver.

BUYING CLASSIC CAMERAS VI

Requiem for a Great Format

by David Silver

"Now cracks a noble heart.

Good night, sweet prince..."

As in Shakespeare's immortal play, when sad Horatio mourns the passing of his beloved Hamlet, soon we may mourn the passing of a great film format.

With the few remaining suppliers of #127 roll film hinting that they may soon discontinue its manufacture, an eighty-year history of success and survival appears to be coming to an end. Indeed, all things must pass, but while #120 roll film still holds its place as the aged king of photographic formats, we must certainly remember #127 as the original crown prince!

It all began in 1912 when the Eastman Kodak Company introduced the Vest Pocket Kodak, the first in a long line of highly successful miniature folding bellows cameras. A marvel of compactness, it was actually much smaller than the majority of modern 35mm cameras available today! When not in use, the "VPK" collapsed into a tiny package only an inch thick and measuring a scant 2 1/2 inches wide by 4 3/4 inches tall. When ready to shoot, the front standard was pulled forward nearly three more inches on intricate trellis struts until it clicked into position with the bellows fully extended. The Eastman Kodak Ball Bearing shutter and simple meniscus achromatic lens provided reliable service, and the overall operation was relatively "user friendly" compared to many of the other folding cameras of that period. With the revolutionary use of lightweight metal alloys throughout its construction, this classic camera's sleek styling makes it an undeniable favorite among collectors today, but, more importantly, it was also Eastman's first vehicle for their new #127 roll film format.

Offering a full-frame image size of 1 5/8 x 2 1/2 inches, #127 roll film promoted a standard for miniaturization in camera design that had never been achieved before. While there were plenty of smaller cameras produced before the VPK, this new film provided a more adaptable and convenient format that other manufacturers would soon adapt into their own product lines. Its initial popularity is easily illustrated in the longevity of so many #127 models and the sheer number of these cameras still available for the collector today. For example, the original 1912 style of the VPK, which you might assume to be a relatively scarce item, was produced in large numbers through 1926 and is really quite common. An example in excellent overall condition can sell for up to $50, with higher premiums for "Special" models, or those with better lenses, and especially for the earliest variants that lack the Autographic feature Eastman Kodak added in 1915.

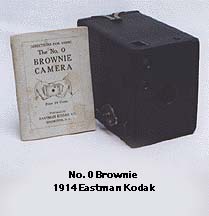

To ensure that this new compact format would be available to photographers of all economic levels, Eastman Kodak was quick to beat their competition when they added a #127 model to their famous line of inexpensive cardboard box cameras. The result was the tiny No. 0 Brownie of 1914. Small enough to rest comfortably on the palm of a man's hand, the No. 0 offered all the no-nonsense simplicity that made the Brownie brand of box cameras so popular, and it stayed in production over twenty years. Although not as common as most of the larger Brownie models, excellent examples can be found in the $20 range and upwards of double that amount with the fancy original box.

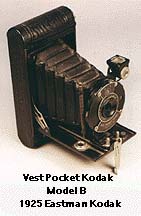

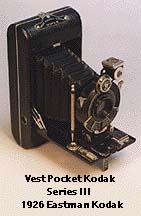

By 1925 many other manufacturers were developing and improving "vest pocket" models, but Eastman Kodak maintained its advantage with a new winning combination of its own. Taking a cue from the overwhelming success of their larger Folding Pocket Kodak cameras, they replaced the original VPK design with the Vest Pocket Kodak Model B. This competent little snapshooter featured a more conventional folding bed, similar to other folding roll film cameras, and a pull-out front standard sporting a basic rotary shutter and meniscus achromatic lens. This was their "amateur" version and it eventually became one of the best selling cameras in history. The following year, with the more serious photographer in mind, Eastman brought out the Vest Pocket Kodak Series III, which was a true miniature "clone" of the bigger Folding Pocket Kodak cameras, equipped with better lenses and shutters. Both updated VPK variations were later available in fancy colors and finishes, often as part of elaborate cased outfits, and were produced into the mid 1930's. The Model B was also the basis for vest pocket versions of the Premo and Hawk-Eye. Today a plain black example of the Model B or Series III in excellent condition will sell in the $50 range, while a fancy colored Petite, Vanity, or Scout version will usually bring three times that amount if they still have their matching colored bellows. Complete cased Ensemble or Vanity outfits, especially with the original boxes, can go for quite a bit more.

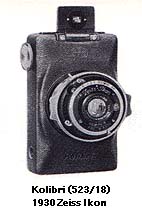

During the Depression, 35mm film became the new "kid" on the photographic block and with it came further miniaturization. However, instead of driving #127 out of the market, manufacturers turned to the older established roll film for alternative designs and formats to increase competition. Zeiss Ikon of Germany, for example, produced a marvelous vest pocket camera for #127 film called the Kolibri. It featured a superior Compur shutter and a choice of exceptional lenses, and its 3 x 4 centimeter half-frame format was nearly 40% larger than 35mm. With great attention to style and detail, the Kolibri's solid body design with plush leather exterior and special fitted case made a striking contrast next to similar sized metallic 35mm offerings. While not as economical or versatile as emerging 35mm models, it was blessed with its own undeniable finesse and charm. Today collectors gladly pay prices in the $300 range for these beauties. And Zeiss Ikon produced a better quality line of miniature box cameras, also for 3 x 4 exposures on #127 film, called the Baby-Box Tengor. Unlike most typical 20th century amateur box cameras, they're uncommon items today and sell for about $75 when found in clean and complete condition. In either case, Zeiss Ikon, like a number of other manufacturers, failed to properly promote these fine products in the face of increasing interest in 35mm and they saw little return from their endeavors. They discontinued the lines after just a few years of production and chose to compete with 35mm in different ways.

Some companies, however, ignored the 35mm threat and used #127 roll film to greater advantage. Franke & Heidecke of Germany, despite already dominating the #120 roll film "twins lens reflex" camera market for many years, offered a #127 alternative as early as 1931. Their Rolleiflex 4 x 4, also known as the "baby" Rolleiflex, was never intended as a discount or stripped down version. Indeed, it was a superior machine for the serious photographer looking for a smaller package, featuring the same quality shutter and optics as their larger versions, and was manufactured right up until World War II. In clean and working condition, these "babies" currently fetch about $300. They were so popular in their day that Franke & Heidecke reintroduced a "gray baby" Rolleiflex 4 x 4 from 1957 to about 1963, a very stylish model that came with a specially fitted gray clam shell case. These sold quite well initially and are common today in the $200 range. A final "black baby" model in 1963 met with little interest

and remains a desirable curiosity for collectors. At the prohibitive prices Franke & Heidecke wished to charge for the camera at that time, #127 roll film in the twin lens reflex format was perhaps an idea past its prime. However, they had already left a legacy of superior product from earlier years for collectors to use and appreciate.

Back in the Depression again, several other German manufacturers did see some success with #127 roll film in more traditional folding camera styles, but not without the occasional unusual feature to gain the public's attention. For example, Foth & Company sought to emulate the sudden success of the Leica 35mm camera when it introduced its Derby camera in 1930 boasting a cloth focal plane shutter and speeds up to 1/500 of a second. Oddly, the rare original model produced images only 24 x 36 millimeters on #127 roll film, the exact same dimensions as a standard 35mm frame! The potential advantage of #127's larger format was therefore lost! The improved version of the Derby in 1931, however, fixed this shortcoming by expanding the film plane to 3 x 4 centimeter half-frame format. But despite its own very adequate Foth Anastigmat lens, it could also be ordered with a Leitz Elmar lens identical to that found on the Leica camera. This was a roll film camera with a serious 35mm identity crisis! They even stocked a special model covered in "lizard skin" rather than leather, similar in effect to the rare Leica Luxus!! Still, the Foth Derby had a distinctive pop-out bellows, later came with a selection of odd rangefinding devices, and managed to survive until about 1942. Amidst all the variations and confusion, I would hazard to say that a clean basic model would cost a collector about $75, while adding a weird lens or weird format or weird anything else would probably double that price.

Now, to sweeten the pot for you collectors, here are a few other comparable vintage miniature folding cameras for #127 roll film that might catch your eye at flea markets, antique swaps and garage sales. The Baldi, Piccochic (a Foth Derby clone!), and Rigona from Balda-Werk; the Dolly Vest Pocket cameras from Certo; the Piccolette (a Vest Pocket Kodak clone) from Contessa; the Vollenda from Nagel-Werk; the rare Makinette from Plaubel; the Ysella from Rodenstock; the Goldi 3 x 4 from ZEH; and so on, and so on! I think you see my point! And, while prices are always negotiable, most of these can be had for under $100 and often closer to $50.

In 1933 Ihagee Kamerawerk took a completely different approach to the #127 format and introduced the Exakta, the first small format "single lens reflex" camera. Appearing in several variations over the next few years, the roll film Exakta was primarily a black beauty that fit snugly in the hands, offered an extremely fast cloth focal plane shutter, provided the modern luxury of through-the-lens focusing, and used the entire 1 5/8 x 2 1/2 inch #127 format to full advantage. Ironically, despite its fabulous features, the Exakta's greatest claim to fame is that it eventually evolved into arguably the most important and influential line of early 35mm system cameras. Therefore, its success was ultimately another dagger into the heart of #127 roll film. Still, the most frequently found version of this classic, the model B, is worth about $300 today.

After World War II fewer manufacturers seemed interested in developing top quality cameras for the #127 format, and the photography market was clearly dominated by 35mm and #120 roll film designs. #127 was viewed as an unnecessary compromise, and most companies seemed disinclined to challenge that situation. Perhaps the most noticeable exceptions occurred in Japan, where a number of the larger manufacturers, such as Minolta, Riken, and Yashica, produced some excellent twin lens reflex cameras for the "4 x 4" format in the 1950's and 1960's. Similar to the "baby" Rolleiflex from Franke & Heidecke that preceded them, these were superior cameras for serious photographers. Unfortunately, despite superb optics and overall high quality, they were no more successful than their later German counterparts and soon disappeared from the market. When these and a few other noble efforts were gone, #127 was eventually relegated to secondary status in the land of cheap snapshooters and plastic box cameras. From there it would be a long and lonely death.

So what went wrong? Why did the photographic market suddenly abandon the #127 format and all its obvious advantages? How could a film that was the basis for so many cameras for so many people from so many companies possibly fail? Certainly, there are plenty of other notable roll film formats that are gone today, but, compared to #127, their demises were hardly as mysterious.

For example, the No. 3A Folding Pocket Kodak of 1903 gave us #122 roll film and the classic 3 1/4 x 5 1/2 inch "post card" format. A zillion of these big friendly folding cameras were made, with relatively few changes or modifications, over the ensuing forty years. It was undeniably one of Eastman Kodak's greatest triumphs. In fact, while the cameras were phased out of production altogether by the end of World War II, so many of the early models remained in the public's hands that Kodak grudgingly kept stores of #122 roll film available until 1971! But the reasons for ceasing production, however, are still perfectly understandable. The "3A" size was truly emblematic of its time, when there was a more leisurely pace to life and photography was a casual pursuit, but by 1945 and the post-war industrial boom it was just too darn slow and clunky. The fast moving world of the 1950's was hardly the place for a camera the size of a small frying pan! In the face of miniaturization, foreign markets, and advanced technology, #122 was more than just a little bit old fashioned. It was downright archaic!

For another example, the Kodak Bantam Camera of 1935 introduced #828 roll film as a more efficient alternative to 35mm cassettes. Designed to use more of the space available on raw 35mm stock, it was a well conceived format, but an otherwise ill advised marketing scheme. Eastman, insisting that this was a format for the future, created some fabulous cameras to use their new "bantam" roll film, but the advantages they offered were subtle at best and they just couldn't sell the idea outside of the United States. Despite the obvious lack of popularity, Kodak forced the issue and continued to produce #828 cameras through 1959, and the film was available until just a few years ago. Ironically, the last laugh belonged to Kodak anyway, although they hardly could have predicted it in the 1930's. Little did anyone know that bantam film would eventually evolve into one of the most lucrative photographic marketing successes in the industry's history. With the same film stock loaded into an ingenious plastic drop-in packet instead of onto a traditional spool in 1963, it would become the #126 instamatic cartridge!

Back to the point, #127 roll film was never "slow and clunky" or obviously "archaic" like #122. Just the opposite, it was small, clean, and quick, yet provided an image area substantially larger than 35mm. And #127 was never just an ill-advised marketing scheme or a format-in-waiting like #828. Instead it was an extremely popular medium for many years that required little initial promotion and inspired confidence among its users. More importantly, photographic manufacturers all over the world gladly embraced the #127 format at first. They recognized its limitless potential, liberally experimented with its application, and exploited it whenever and wherever they could. Yet despite all of this, #127 roll film was somehow a victim of its own prosperity, as it was never perceived to belong to any one particular niche. Longevity grows from stability, and perhaps the use of #127 was spread too thinly for the comfort level of the 1960's market. Whatever the case, it was a great format, and while it never achieved the level of success that #120 roll film attained, as the conventional standard of the photographic industry, it saw its share of heroic endeavors in the evolution of camera technology. Who could have known that it would prove to be a "tragic" hero? So, yes, our crown prince of roll film formats may soon be gone, but, oh, what a royal legacy it left behind for us to collect and acquire and preserve! Imagine, if it had only been king!

Copyright © 1996, 2002, David Silver. All rights reserved.

This article first appeared, in this edited form from a longer original manuscript, in the March 11, 1996, issue of Photo Shopper magazine. If you'd like to reprint the article, acquire secondary rights, or inquire on the availability of new articles, please feel free to contact the author at silver@well.com, thank you!

BACK to the International Photographic Historical Organization article contents page!

GO TO the International Photographic Historical Organization home page!

CONTACT the author, David Silver, for more information!

|